STREET TALES. ALPO MARTINEZ.

Street Tales,

Grisly and Raw; Grim True-Crime Magazine Hits Home With Inmates

By CHRIS HEDGES

Published: December 06, 1999

Published: December 06, 1999

Alberto

Martinez, known as Alpo, once one of the biggest cocaine dealers in Harlem and

Washington, was on the phone with Antoine Clark, the editor, reporter and

photographer of F.E.D.S. magazine.

Mr.

Clark paced back and forth, slipping into prison jargon as he interviewed Mr.

Martinez, who was talking from a maximum-security cell in a prison outside New

York that he did not want named.

Although

Mr. Clark had to cajole and coax details out of him, Mr. Martinez wanted

F.E.D.S. to publish his descriptions of some of the 14 murders to which he had

confessed before he became a government witness.

Criminal

confessions and tales of the dark side of hip-hop life are a staple of

F.E.D.S., for Finally Every Dimension of the Streets. The gruesome authenticity

of these interviews has won a fast audience on Rikers Island, where inmates

pass photocopies through the cellblocks.

The

articles may horrify some readers, as the grisly remembrances rarely end in

mitigating expressions of regret.

But

Mr. Clark sees them as cautionary tales -- look at what the gangster life can lead

to -- and the truth is in the violent details.

Mr.

Martinez's tales were as violent as any Mr. Clark had ever heard.

One

murder Mr. Martinez described was that of a boyhood friend, Richard Porter, in

January 1990. Mr. Martinez suspected that his friend was cutting in on his drug

deals. ''Yes, I killed Rich,'' he told Mr. Clark. ''It wasn't personal. It was

business.

''Rich

lied to me about something there was no reason to lie about. I gave him the

opportunity to tell me the truth not once, but twice.'' Mr. Martinez said an

accomplice then shot Mr. Porter twice. ''He didn't die, so I shot him in the

head.''

Mr.

Martinez said that he and his chief hit man drove the body from Harlem to City

Island, where they dumped the corpse in the bushes.

During

a pause in his interview, Mr. Martinez said he was speaking with F.E.D.S.

because it reached everyone he cared about.

''I

talk to them because they talk the language of the street,'' Mr. Martinez said.

''F.E.D.S. is on the inside looking out. Everyone else who writes about us is

on the outside looking in.''

F.E.D.S.

is something of a sensation in the prison system, which accounts for more than

90 percent of its 7,000 paid subscribers.

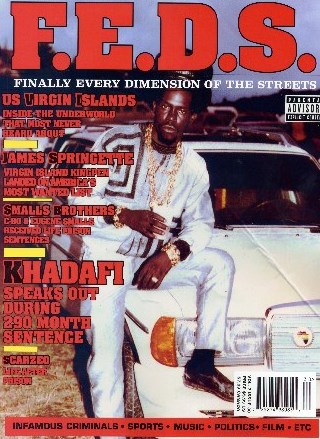

On

its cover the magazine promises articles on ''convicted hustlers, street thugs,

fashion, sports, music and film.'' It carries a ''parental advisory'' label.

But

Mr. Clark believes that his gory reporting on street violence goes a long way

toward deflating the criminal myths promoted by some rap recording stars.

''I

want to show the other side of this life,'' he said. ''I want to show what

happens to these gangsters when things go wrong, as they almost always do.''

F.E.D.S.

reports off the streets of Harlem and the Bronx in a way other magazines like

Source, Vibe and Blaze do not. In addition to criminal confessions, F.E.D.S.

prints the doings of the hottest hip-hop artists and what's going on in the

neighborhoods, all spewed out in raw slang. Each issue of the quarterly sells

out within days of hitting newsstands.

Mr.

Clark, 30, calls news sources on a cell phone in the old car that is his

office, and he gets his mail at a post office box on the Upper East Side. He

carries around stacks of letters from prison, most with government-issued

checks from correctional facility accounts, demanding copies of the three

preceding issues of the magazine, a demand he is unable to meet because there

are no copies left. But he is not eager to anger a readership that has a

history of violent behavior, so he is planning to reprint all the past cover

articles in an issue scheduled for publication next week.

In

1987, when Mr. Clark was in the 11th grade, he dropped out of Adlai E.

Stevenson High School in the Bronx, not sure what to do with his life. Not long

after that, he was standing outside a Bronx roller-skating rink, the Skate Key,

when a dispute broke out on the sidewalk. One man, about six feet away, pulled

out a pistol and fired wildly, missing his intended victim, but wounding a

young girl and Mr. Clark, who was shot in the back and the leg.

''I

tried to run behind a van but fell,'' he said. ''I lay on the ground and could

not move my legs. Then I felt the burn of the bullets.''

His

recovery was glacial. For almost two years he used his arms to pull himself

around his mother's apartment, dragging his legs behind him. As he progressed,

he began using a walker, slowly shifted to crutches, and finally to a leg

brace, which was removed two years ago. He has no feeling below his left knee,

and a bullet is still lodged just under his spine.

It

was during his recuperation, reading and rereading newsmagazines and poring

over the dictionary (a habit that led to his ability to spit out precise

definitions at will), that he dreamed of his own magazine. But unlike Time or

other newsmagazines that cater to, as he put it, ''the upper business elite,''

he wanted to write for the people he knew on Gun Hill Road in the Bronx.

''I

wanted to show what was real, what was going on,'' Mr. Clark said. ''No one was

doing that. I've seen these people get killed off, one after the other. I know

how these big criminals in prison cry at Christmas and at night because they

are alone. It seemed time to tell about real life and tell about it in the

language people use.''

The

problem was money. His injury had ended his cleaning job at the Saks Fifth

Avenue warehouse in Yonkers. He floated in and out of less physically demanding

jobs at a barbershop and an upholstery store.

But

he kept planning his magazine. He had stickers printed with his first cover,

and after midnight he plastered them around the neighborhood. In his spare time

he took pictures and taped interviews.

''I

used to meet people who claimed they had read it,'' Mr. Clark said. ''Everyone

knew the name. People wouldn't believe me when I told them it didn't exist.''

Finally

he landed a job managing a local rap group, Money Boss Players, and when the

group signed a record deal, he took $7,000 from his fee and printed 5,000

copies of F.E.D.S. The first issue was 16 pages. There were no advertisers. The

cover price was $3.50.

''I

picked the copies up on 21st Street and my first drop-off was on 125th

Street,'' he said. ''I smiled all the way there. I kept touching the front

page. When I got to the newsstand I started passing them out for free just

because I wanted people to have it.''

The

magazine, with glossy color photos, is rough-edged in its use of language, but

it shows what tenacity and persistence can achieve. Mr. Clark, who is never

without his camera and tape recorder, has written detailed articles about

big-time criminals in Harlem and the Bronx, including a long article on Nicky

Barnes, known as the Black Godfather, a heroin kingpin of the 1970's. Mr.

Barnes was convicted of major federal narcotics violations, and in 1978 was

sentenced to life in prison without parole.

After

the Barnes article ran in March, Mr. Clark received a letter from the Federal

Bureau of Investigation. The F.B.I., listing a page number that showed Mr.

Barnes and some of his colleagues at a party in Manhattan in the 1970's,

accused the magazine of endangering undercover government agents. Mr. Clark

said he did not know the identity of most of those sipping drinks with Mr.

Barnes, so had taken the precaution of blanking out the eyes with strips

reading ''warning.''

Mr.

Clark hunts down candid photos, many turned over by those he writes about, that

show the city's most notorious gangsters living the high life in luxury hotels,

as well as bloody bodies left behind on street corners.

In

each issue, F.E.D.S. prints an ''R.I.P.'' page for those killed in the latest

street violence, as well as pictures of heroin addicts at local shooting

galleries with the headline: Drugs Kill.

''It

is a unique magazine,'' said David Mays, the owner of Source, the country's

second-largest music magazine, after Rolling Stone.

''It

taps into street culture and in some cases criminal culture, but does not

glorify it. It reminds me of how I started out 11 years ago when I began

publishing a two-page newsletter with $250.''

Mr.

Clark's wife, Monique, edits the copy, and often seems bemused by as well as

proud of her husband. Two friends are the rest of the staff: David Farquharson,

29, is in charge of advertising, and Arthur Gray, 30, supervises distribution.

The

fall issue has 72 pages, including 30 pages of advertising, and will have a

press run of 30,000 copies. It cost $81,000 to produce.

Mr.

Clark has turned down a few offers for investment, in part because of a fear of

outside control. But Mrs. Clark wields a lot of power. After she said a picture

of a stripper wearing only black boots was tasteless, she forbade her husband

to print any more such photos.

Some

interview subjects have had second thoughts about speaking freely. In the

second issue, published in the spring, Damon Dash, who runs Roc-A-Fella

Records, regretted mentioning the names of street thugs for an article. Mr.

Clark spent most of the night before distribution going through the thousands

of copies to black out the names by hand.

''The

big advantage of not having an office,'' Mr. Clark said, ''is not worrying

about a brick through the window. I started at the bottom. I don't pretend to

be too advanced. When you are at the bottom you reach everybody. It's best, if

you want to keep reaching them, to stay there.''

.jpg)

We feature criminals and their exploits on this blog in order to show the influence of street culture on pop culture today. The idea being those who love to glorify said culture may see the realities of that life from the view of jailed gangsters and how many turn "snitch" and rat out their comrades.

ReplyDelete